what does it mean to be white robin diangelo audiobook

What Does Information technology Hateful to Be White?

Developing White Racial Literacy – Revised Edition

Textbook XI, 371 Pages

Series: Counterpoints, Volume 497

Summary

What does information technology mean to exist white in a society that proclaims race meaningless, yet is deeply divided by race? In the confront of pervasive racial inequality and segregation, most white people cannot answer that question. In the second edition of this seminal text, Robin DiAngelo reveals the factors that make this question so difficult: mis-instruction nigh what racism is; ideologies such equally individualism and colorblindness; segregation; and the belief that to be complicit in racism is to exist an immoral person. These factors contribute to what she terms white racial illiteracy. Speaking as a white person to other white people, DiAngelo clearly and compellingly takes readers through an analysis of white socialization. Weaving inquiry, assay, stories, images, and familiar examples, she provides the framework needed to develop white racial literacy. She describes how race shapes the lives of white people, explains what makes racism so hard to come across, identifies common white racial patterns, and speaks back to popular narratives that work to deny racism. Written equally an accessible overview on white identity from an anti-racist framework, What Does It Mean to Be White? is an invaluable resources for members of diversity and anti-racism programs and study groups, and students of sociology, psychology, teaching, and other disciplines. This revised edition features two new capacity, including ane on DiAngelo'due south influential concept of white fragility. Written to be accessible both within and without academia, this revised edition besides features discussion questions, an index, and a glossary.

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Almost the author(due south)/editor(southward)

- Most the book

- This eBook tin be cited

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Affiliate one: Race in Education

- Chapter 2: Unique Challenges of Race Education

- Affiliate 3: Socialization

- Chapter 4: Defining Terms

- Chapter 5: The Bike of Oppression

- Chapter vi: What Is Race?

- Chapter 7: What Is Racism?

- Chapter 8: "New" Racism

- Chapter 9: How Race Shapes the Lives of White People

- Chapter x: What Makes Racism So Hard for Whites to See?

- Chapter eleven: Intersecting Identities—An Instance of Grade

- Chapter 12: Common Patterns of Well-Meaning White People

- Affiliate 13: White Fragility

- Affiliate 14: Popular White Narratives That Deny Racism

- Affiliate xv: Stop Telling That Story! Danger Discourse and the White Racial Frame

- Chapter 16: A Note on White Silence

- Chapter 17: Racism and Specific Racial Groups

- Chapter xviii: Antiracist Education and the Road Ahead

- References

- Glossary

- Index

- Series index

| 9 →

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I extend my most heartfelt cheers to the numerous friends and colleagues who supported me in this project. Jason Toews, for the hours of astute and vigilant editing y'all generously donated; my colleagues Anika Nailah, Özlem Sensoy, Holly Richardson, Carole Schroeder, Malena Pinkam, Lee Hatcher, William Borden, Kelli Miller, Ellany Kayce, Darlene Flynn, Deborah Terry, Jacque Larrainzar, Darlene Lee, Sameerah Ahmad, Nitza Hidalgo, and Kent Alexander for your support, insight, and invaluable feedback. Cheers Amie Thurber for your perceptive and detailed reading of the final draft and assistance with the word questions. Thank you Brandyn Gallagher for your insight and patience in working to raise my awareness of cis-supremacy. Cheers to Dana Michelle, Thalia Saplad, and Cheryl Harris for all I learned from you in the beginning of this journey.

Cheers to all of the scholars whose work has been foundational to my understanding of whiteness, particularly Peggy McIntosh, Richard Dyer, Charles Wright Mills and Ruth Frankenberg. Any errors or omissions in interpreting or crediting that piece of work are my ain.

A special thank you to Robin Boehler—a swain white ally—for the countless hours nosotros spent debriefing our grooming sessions and working to put the racial puzzle together. Your back up and brilliance were invaluable. ← ix | 10 →

Thanks Todd LeMieux for all of your design and graphic work, Andrea O'Brian for your Frames of Reference illustration, and Katherine Streeter for the beautiful cover art.

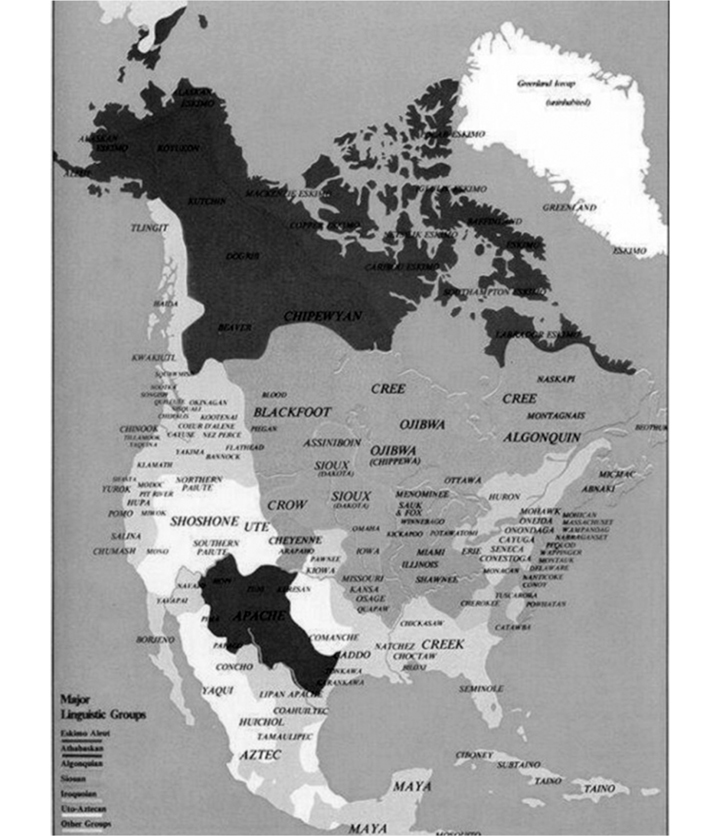

This text addresses whiteness within the context of what is now known as the United States, originally known as Turtle Island past some Indigenous peoples. The theft of Indigenous lands was the starting point of our current racial system. A central argument of this book is that we must know where we came from in order to empathise where we are now. For a powerful overview of this history, see Bury My Centre at Wounded Knee and A People'southward History of the Usa. In honor of the Indigenous peoples whose bequeathed territories l stand on and write from, I offering my sincerest respect. ← 10 | xi →

Figure 1. Map of Indigenous peoples at time of 15th-century European contact.

| 1 →

INTRODUCTION

I grew upward in poverty, in a family in which no 1 was expected to go to college. Thus I came tardily to academia, graduating with a BA in Sociology at the age of 34. Unsure what I could do with my caste, I went to my college'south career eye for aid. After working with the career counselors for several weeks, I received a phone call. The advisor told me that a chore announcement had just arrived for a "Diversity Trainer," and she thought I would be a good fit. I didn't know what a Diversity Trainer was, merely the job clarification sounded very exciting: co-leading workshops for employees on accepting racial difference. In terms of my qualifications, I have always considered myself open-minded and progressive—I come up from the West Coast, drive a Prius, and shop at natural food markets such every bit Whole Foods and Trader Joe's (and always bring my own bags). I volition acknowledge that I have on occasion told an ethnic joke or two (but never in mixed company) and that I was often silent when others told similar jokes or made racist comments. Only my silence was usually to protect the speaker from embarrassment or avoid arguments. Thus, confident that I was qualified for the diversity trainer position, I practical and received an interview.

The interview committee explained that the State's Section of Social and Health Services (DSHS—the "welfare" department) had been sued for ← i | ii → racial discrimination and had lost the adjust. The federal government had determined that the section was out of compliance regarding serving all clients equally across race and, as part of the settlement, had mandated that every employee in the state (over 5,000 people) receive sixteen hours (2 total workdays) of multifariousness training. DSHS hired a training company to design and deliver the trainings, and this company wrote the curriculum. Part of the design was that inter-racial teams would deliver the trainings. They needed 40 trainers to be sent out in teams of 2. The interview committee, composed primarily of other (open up-minded) white people such every bit myself, agreed that I was qualified, and I got the job. Initially elated, I had no idea that I was in for the about profound learning curve of my entire life.

I showed up for the Train-the-Trainer session with 39 other new hires. We would be working together for 5 full days to acquire the curriculum and become set to fan out across the land and lead the workshops. The challenges began almost immediately. On the first twenty-four hours, every bit we sat in the opening word circumvolve, one of the other white women chosen out, "All the white racists raise your hand!" I was stunned every bit virtually every white hand in the room shot up. I was smart enough to realize that for some unfathomable reason this was the "party line" and that I should heighten my hand like everyone else, only I just couldn't. I was not racist, and there was no manner I was going to identify myself as such. Over the side by side five days we spent many hours engaged in heated discussions about race.

This was the first time in my life that I had e'er talked about race in such a directly and sustained way with anyone, and I had never discussed race before in a racially mixed group. My racial paradigm was shaken to the core as the people of color shared their experiences and challenged my limited racial perspective. Indeed, I had never earlier realized that I had a racial perspective. I felt similar a fish being taken out of water. The contrast betwixt the mode my colleagues of color experienced the world and the mode I did worked similar a mirror, reflecting back to me not only the reality that I had a racial viewpoint, but that it was necessarily limited, due to my position in society. I did not see the world objectively as I had been raised to believe, nor did I share the same reality with everyone around me. I was non looking out through a pair of objective eyes, I was looking out through a pair of white eyes. By the end of the 5 days I realized that regardless of how I had always seen myself, I was deeply uninformed—even ignorant—when it came to the complexities of race. This ignorance was not benign or neutral; information technology had profound implications for my sense of identity and the fashion I related to people of color. ← two | 3 →

The next point on my learning curve began when my co-trainer (a black woman) and I began leading the workshops in DSHS offices beyond the country. I had been expecting these sessions to exist enjoyable; after all, nosotros would be exploring a fascinating and important social issue and learning how to bridge racial divides. I have always establish self-reflection and the insights that come from it to exist valuable, and I assumed that the participants in the workshops would feel the same way. I was completely unprepared for the depth of resistance nosotros encountered in those sessions. Although there were a few exceptions, the vast majority of these employees—who were predominantly white—did not want to be in these workshops. They were openly hostile to us and to the content of the curriculum. Books slammed down on tables, crossed arms, refusal to speak, and insulting evaluations were the norm.

We would ofttimes lead workshops in offices that were 95–100% white, and yet the participants would bitterly complain about Affirmative Action." This would unnerve me every bit I looked around these rooms and saw merely white people. Clearly these white people were employed—we were in their workplace, after all. There were no people of color hither, yet white people were making enraged claims that people of colour were taking their jobs. This outrage was not based in any racial reality, still obviously the emotion was real. I began to wonder how we managed to maintain that reality—how could we not encounter how white the workplace and its leadership was, at the very moment that we were complaining virtually not being able to get jobs considering people of color would be hired over "us"? How were we, as white people, able to enjoy and so much racial privilege and dominance in the workplace, yet believe so deeply that racism had changed direction to now victimize usa? Of course, I had my own socialization as a white person, then many of the sentiments expressed were familiar to me—on closer reflection I had to acknowledge that I had held some of the same feelings myself, if just to a lesser degree. But I was gaining a new perspective that allowed me to stride dorsum and brainstorm to examine my racial perceptions in a way I had never before been compelled to exercise.

The freedom that these participants felt to express irrational hostility toward people of color when there was only one person of color in the room (my co-facilitator) was another aspect of how race works that I was trying to understand. Every bit a adult female I felt intimidated when a white man erupted in acrimony. But at least I wasn't the only woman in the room, and the target was ultimately not me, but people of colour. The lack of white concern for the bear upon our anger might accept on my co-facilitator, who ofttimes was the simply person of color in the room, was confusing. Driving home, I saw the devastating effect of this ← 3 | 4 → hostility on my co-facilitator as she cried in hurt, anger, and frustration. How could these white participants not know or care about this impact? How could we forget the long history of aroused white crowds venting racial rage on an isolated person of colour? Where was our collective retentivity? And what about the other white people in the room, those not openly complaining but supporting the complainers nonetheless through their silence? How might the ability to act and so insensitively across racial lines depend on the silence of other whites? If we every bit white people did not speak up to challenge this, who would? How much more emotionally, intellectually, and psychically draining was it for my co-facilitator to speak dorsum to them, than for me? Even so it had ever been socially taboo for me to talk straight about race, and in the early days of this work I was too intimidated and inarticulate to raise these questions.

We had five,000 employees across the state to train, and the project took 5 years to complete. As the years went past and I was involved in hundreds of discussions on race, clear and consistent patterns emerged, illustrating the means in which white people conceptualize race and thus enact racial "scripts." Once I became familiar with the patterns, it became easier for me to understand white racial consciousness and many of the ideas, assumptions, and beliefs that underpin our understanding of race. I also had the rare gift of hearing the perspectives of countless people of colour, and—in time—I became more articulate about how race works and less intimidated in the face of my swain whites' hostility—be it explicitly conveyed through aroused outbursts or implicitly conveyed through silence, aloofness, and superficiality.

Because I grew up poor and understood the pain of being seen as inferior, prior to this experience I had always thought of myself as an "outsider." But I was pushed to recognize the fact that, racially, I had always been an "insider"; the culture of whiteness was so normalized for me that it was barely visible. I had my experience of course marginalization to draw from, which helped tremendously as I struggled to sympathize racism, simply equally I became more than conversant in the workings of racism, I came to understand that the oppression I experienced growing upwards poor didn't protect me from learning my place in the racial hierarchy. I now realize that poor and working-class white people don't necessarily accept any "less" racism than middle- or upper-class white people. Our racism is just conveyed in dissimilar ways, and we enact it from a unlike social location than the middle or upper classes. (I will discuss this in more than depth in Affiliate xi.)

As the foundation of the white racial framework became clearer to me, I became quite skilled at speaking back in a manner that helped open up up and shift perspectives. Although I learned a tremendous amount from all of the trainers ← 4 | 5 → I worked with over those years, by the end of that contract there were simply two of us left: myself as a white trainer and my African American co-trainer Deborah Terry-Hays. I had been given an extraordinary gift in having the honor of working with Deborah, a brilliant, compassionate, and patient mentor. She and I went on to atomic number 82 like workshops with other groups, including teachers, municipal workers, and police officers. Over the years I realized that I had been given an opportunity that few white people e'er had—to co-lead discussions on race on a daily basis. This piece of work had provided me with the power to empathize race in a profoundly more than complex and nuanced style than I had been taught by my family, in schoolhouse, from the media, or past society at large. Cypher had previously prepared me in any fashion to think with complexity about race. In fact, the way I was taught to run into race worked beautifully to hibernate its power as a social dynamic.

I wanted to apply my new knowledge beyond these workplace discussions in order to affect a wider audience. I decided to earn my doctorate in Multicultural Education and Whiteness Studies so that I could disseminate what I had learned through teaching and writing. I completed my doctorate in 2004. My graduate study added more layers to my knowledge—6 additional years of scholarship and written report. I now had empirical research and theoretical frameworks to back up all I had experienced in my years of practice. In graduate school I co-led courses that trained students to lead interracial dialogues. For my dissertation study, I gathered an interracial group of students together to engage in a series of discussions on race over a 4-week period. A trained interracial team of facilitators led the discussions. I sat quietly in the back, observing while the sessions were video-recorded. This observation was the showtime time I was non in the position to either lead or participate in the discussion, and the opportunity to simply detect provided nonetheless more than insight into how whites "do" race.

I now understand that race is a profoundly circuitous social arrangement that has cypher to practise with being progressive or "open up-minded." In fact, we whites who see ourselves as open-minded tin actually be the nigh challenging population of all to talk to about race, because when nosotros believe we are "absurd with race," we are not examining our racial filters. Further, because the concept of "open-mindedness" (or "colorblindness," or lack of prejudice) is so important to our identities, we really resist any proffer that there might exist more going on below the surface, and our resistance functions to protect and maintain our racial blinders and positions.

Today I am a writer, speaker, consultant and sometime associate professor of teacher pedagogy. Whether I am leading classes or workshops for college ← v | 6 → students, academy kinesthesia, social workers, government workers, youth, or private sector employees, each population I work with considers itself somehow unique, and when I am brought in I am frequently told that I must know such and such in guild to understand this specific group. Yet in my years of experience working with all of these populations, the racial patterns are remarkably consequent. The specific norms of the grouping may vary—some groups may be more than outspoken than others, or the discussion may centre on education versus business, or at that place may have been some past conflicts I should know about—only the larger guild has collectively shaped the states in very predictable ways regarding race. Thus, although this book begins with the case of the didactics force—because didactics is such a principal site of racial socialization and my field of study—the larger points employ across all disciplines. I inquire readers to make the specific adjustments they remember are necessary, rather than decline the show considering it isn't specifically based in their context. Please note: This book is grounded in the context of the United states of america and does not accost nuances and variations within other socio-political contexts.

The Dilemma of the Main's Tools

Audre Lorde (1983), a writer, poet and activist, wrote that "The master's tools will never dismantle the master's house" (p. 94). She was critiquing feminists of the time who claimed to stand for all women merely who focused their concerns on white, centre-course women. This focus rendered women of color invisible and reinforced the race and form privilege enjoyed past white, middle-class feminists. Lorde and other feminists of colour argued that race, class, and gender were inseparable systems and must exist addressed together. She argued that by non addressing race and class, these feminists were really reinforcing the system of patriarchy and its divisions—re-inscribing racism and classism (amidst other forms of oppression) in the proper noun of eliminating sexism.

Lorde's famous quote also speaks to the dilemma of challenging the system from within. For case, can i authentically critique academia while employed past information technology and thus invested in it? This is one of the major challenges I face as a white person writing virtually race. While my goal is to interrupt the invisibility and deprival of white racism, I am simultaneously reinforcing information technology by centering my voice as a white person focusing on white people. Although some people of color appreciate this, others see it equally self-promoting and narcissistic. This is a dilemma I take not all the same resolved, merely at this point in my journey toward greater racial awareness and antiracist action, I believe the ← vi | 7 → need for whites to work toward raising their own and other whites' consciousness is a necessary first step. I also sympathize and acknowledge that this focus reinforces many problematic aspects of racism. This dilemma may not brand sense to readers who are new to the exploration, simply it may later on.

Another "master'southward tools" dilemma I confront is that race is a deeply circuitous socio-political system whose boundaries shift and adapt over time. As such, I recognize that "white" and "people of color" are not discrete categories and that nested within these groupings are deeper levels of complexity and difference based on the various roles assigned past dominant society at various times (i.east., Asian vs. Black vs. Latino vs. Immigrant; Jewish vs. Gentile; Muslim vs. Christian). By speaking primarily in macro-level terms—white and people of color—I am reinforcing the racial binary and erasing all of the complexity within and between these categories. For example, what about bi- or multiracial people? What nigh a religion (e.thou., Islam), which in the current post-9/xi era has been racialized? As volition be discussed, race has no biological meaning; it is a social idea. Therefore, one'due south racial feel is in large part dictated past how ane is perceived in order. Barack Obama is a clear example. Although he is equally white and black in current racial terms, he is defined as black considering he looks blackness and therefore (at to the lowest degree externally) volition have more of a "black experience"; society will respond to him every bit if he is black, not white.

Thus, for the purposes of this express analysis, I use the terms white and people of color to indicate the two macro-level, socially recognized divisions of the racial hierarchy. I ask my readers who don't fall neatly into i or the other of these categories to apply the general framework I provide to their specific racial identity (I will explore specific racial groups in more depth in Chapter 17). Again, at the introductory level my goal is to provide basic racial literacy and, equally such, agreement the relevancy of the racial binary overall is a get-go step, admitting at the cost of reinforcing it. To move beyond racial literacy to develop what might be thought of as racial fluency, readers will need to proceed to study the complexities of the racial construct.

Chapter Summaries

Chapter 1: Race in Education

This chapter provides an overview of current demographic trends in instructor educational activity. I explain why I believe that nigh white teacher education students ← 7 | 8 → (like most whites in general) are racially illiterate. I share some of my nigh common student essays on the question of racial socialization in guild to illustrate white racial illiteracy. The challenges of a growing white teacher teaching population are discussed.

Chapter 2: Unique Challenges of Race Didactics

This chapter clarifies the differences between opinions on race and racism that all of the states already concur, and informed noesis on race and racism that only develops through ongoing report and do. The common conception of racism as a practiced/bad and either/or proffer is challenged. An overview of race and whiteness as social constructs that take developed and changed over time is provided.

Affiliate 3: Socialization

This chapter explains the power of socialization to shape our identities and perspectives. Using popular studies, I show the means in which our cultural context functions as a framework through which we filter all of our experiences. This filter is so powerful it can shape what we come across (or what nosotros believe we see). This chapter volition begin to challenge the concept of unique individuals outside of socialization and unaffected past the messages we receive from myriad sources.

Chapter 4: Defining Terms

This chapter provides a shared framework for defining key terms such every bit prejudice, discrimination, systematic oppression, and racism. Differentiation is made betwixt dynamics that operate at the individual level (i.east., prejudice and discrimination) and systematic oppression, which is an embedded and institutionalized organisation with collective and far-reaching furnishings. This chapter provides the overall theoretical framework for understanding racism.

Chapters 2, three, and 4 are adapted from Is Everybody Actually Equal? An Introduction to Fundamental Concepts in Disquisitional Social Justice Instruction past Sensoy & DiAngelo (2012). ← eight | ix →

Chapter 5: The Bicycle of Oppression

This chapter continues the discussion of oppression. The elements that constitute oppression are explained: the generation of misinformation; acceptance past guild; internalized oppression; internalized authorisation; and justification for further mistreatment. The handling of children with learning disabilities (a form of ableism) is used to illustrate each point on the cycle.

Chapter 6: What Is Race?

A cursory historical overview of the evolution of race as a social construct is provided. Dynamics of perception are discussed. The interaction between ethnic identity—eastward.thou., Jewish or Portuguese—and race is explored. The development of white every bit a racial identity is traced over time. I introduce the thought of whiteness as a form of property with material benefits.

Affiliate 7: What Is Racism?

Details

- Pages

- 11, 371

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781433137785

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781453918487

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781433137792

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9781433131103

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2017 (March)

- Tags

- Racism Colorblindness Socialization White racism White socialization Bicycle of Oppression Mis-instruction near racism

- Published

- New York, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, Frankfurt am Principal, Oxford, Wien, 2016. 11, 368 pp., num. b/w ill.

Biographical notes

Robin DiAngelo (Author)

Robin DiAngelo received her PhD at the University of Washington, where she was twice honored with the Student's Choice Award for Educator of the Yr. Her concept of white fragility has influenced the national soapbox on race. She has published widely in both mainstream and academic venues.

Source: https://www.peterlang.com/document/1054721

0 Response to "what does it mean to be white robin diangelo audiobook"

Post a Comment